On Bloomberg

Bolsonaro Was Not Elected to Take Brazil as He Found It

Latin America’s biggest democracy has a bigger global role to play.

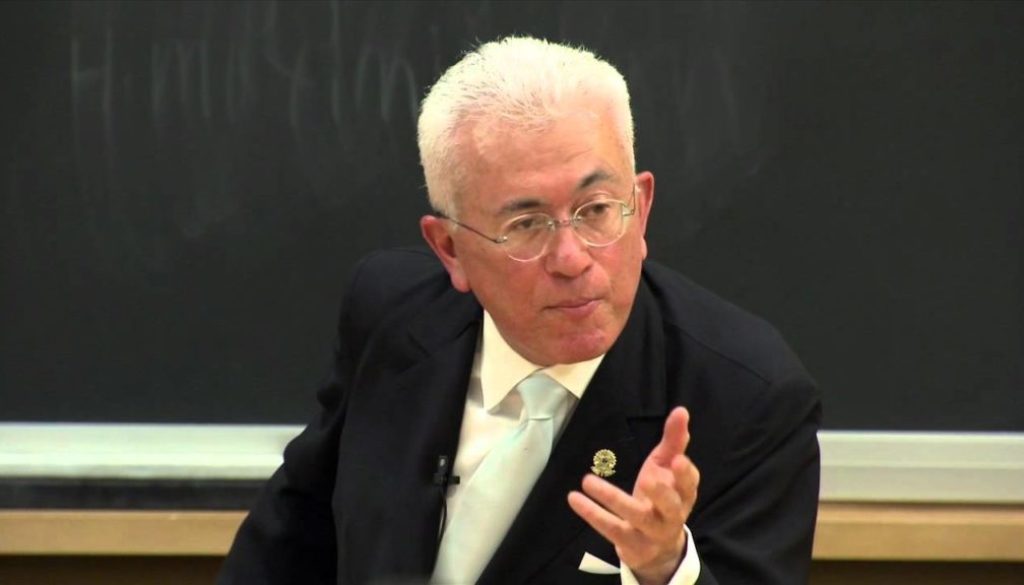

By Ernesto Araujo, minister of Foreign Relations of Brazil

7 de janeiro de 2019 11:00 BRST

“Brazilian foreign policy cannot change.” That is how a Brazilian politician summarized his dislike for the foreign policy of President Jair Bolsonaro and myself. Those views are representative of people who have been so traumatized by the shambolic, far-left foreign policy of the governments of Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva and Dilma Rousseff (2003-2016) that they prefer inaction and indifference to any attempt to make Brazil a global player again. They are so used to bad change that they would rather not risk any change at all.

Those people think the only alternative to Lula’s disaster in foreign policy is to think small, repeat United Nations talking points and try to do some trade. They strive for golden mediocrity. They want Brazil to accept “the world as we found it,” to paraphrase the famous expression of Ludwig Wittgenstein.

That reference is found in paragraph 5.631 of the “Tractactus Logico-Philosophicus,” where the Anglo-Austrian philosopher asserts: “There is no such thing as the subject that thinks and entertains ideas.” That sort of avant-la-lettre post-modern deconstruction of the human subject, and denial of the reality of thought, is thus associated with the renunciation of one’s own capacity to act and influence the world, implicit in the pessimism of “taking the world as we found it.” Those are the philosophical roots of our current globalist totalitarian ideology. By denying independence of thought and the substance of ideas, it manages more and more to dominate the human self as it dictates to people: “you don’t deserve freedom because you don’t exist, you don’t exist as an independent self, you are just the sum of the parts of your body and your ideas are just social constructs, so shut up.”

I don’t like Wittgenstein.

President Bolsonaro was not elected to take Brazil as he found it and to leave it there. He was not elected to take Brazilian foreign policy as he found it, to raise the flag of “pragmatism” perfunctorily, and go home. This is not what the Brazilian people—thinking, independent selves with their own passions and ideas, and not post-modern automata—want and deserve.

Brazilian foreign policy must change: this is part of the people’s sacred mandate entrusted to Jair Messias Bolsonaro.

We are convinced that Brazil has a much larger role to play in the world than the one we currently attribute to ourselves.

We want to promote freedom of thought and freedom of expression around the world. This is essential to promote any other sort of change and any other sort of freedom. Bolsonaro’s election in Brazil was only possible because people could freely exchange their ideas and express their feelings unencumbered by mainstream media’s straitjacket. This lesson is priceless.

Unfortunately, today’s world has countries where thought is directly controlled by the state. It also has countries, mainly in the West, where thought is indirectly and insidiously controlled by the media and academia, leaving very few places untouched by Wittgensteinian death-of-the-subject oppression. Brazil has now shown that it is possible to break free and, through the sheer force of speech, transform the political reality of a country of 200 million people and peacefully dismantle a decades-old system of crime and corruption with courage, determination and sincerity.

We also want to promote peace and security in our region and everywhere. But you don’t promote peace and security by pretending that the threats you face either don’t exist or can’t realistically be addressed. You have to face the threats, and the main one comes from non-democratic regimes that export crime, instability and oppression. You can’t simply wish away dictatorships such as Venezuela and Cuba. Especially when you don’t even wish. Especially when you let them preserve and extend their power, with the excuse that this is “the world as we found it” or “the natural march of things.”

And we want, of course, to expand trade. Brazilian trade policy, as part of our foreign policy, has slumbered for too long. We are determined to negotiate trade, investment and technology deals with all our partners, in an ambitious and creative way, exploring different models with different partners, always with the concrete needs of the productive sector in mind.

Critics would say that by talking about freedom and democracy, and by taking those concepts seriously, we are ideological. They would argue that the advocacy of freedom and democracy will jeopardize our trade. It would be a sad world if this were the case. But I am convinced that a much more assertive Brazil, a country speaking with its own voice and not just dubbing in someone else’s, will be a much better partner—in trade and in any other area.

Some people think our marketing approach should be: “Look, I’m Brazil. I don’t think anything. I don’t have any ideas. Just like Wittgenstein’s deconstructed subject, I don’t have a self. I don’t bother anyone. Trade with me!”

But this doesn’t work. No one respects such behavior, and you don’t reach good trade deals when there is no respect. Look at China. China unapologetically defends its system, asserts its national interests and identity, its specific ideas about the world—and everyone does more and more trade with China. Why should other countries be required to sign up to certain ideas before being considered good trade partners? Should we renounce our commitments to freedom and democracy when others are not required to renounce their commitments to their systems?

Brazil will show that you can increase your share in international trade and investment flows even as you confidently step onto the world stage to defend freedom, speaking with your nation’s own voice.

Brazilian foreign policy can change, and the world can change. We don’t have to take them as we found them.

Elílio

10/01/2019 - 13h16

Eu queria ver o ministro criticando a China comunista como ele criticou Cuba e Venezuela.

Robert Roal

08/01/2019 - 15h48

Look, I am Brazilian, I have a lot of stupid ideas and I do not respect anything. By the way, forget all you know about “Pacta sunt servanda”, we do not give a dam to human rights treaties. What to say about this shit of global warming? Brazil above all and god above everybody. É nóis. Trade with me!

Alex

07/01/2019 - 19h21

ERNESTO ARAÚJO NÃO SABE DE BRASIL

https://novoexilio.blogspot.com/2019/01/chao-de-amendoas-por-alexandre-meira.html

cOMPARTILHE

Benoit

07/01/2019 - 18h53

O sujeito é megalomaníaco, paranóico. O resultado é cômico e patético. Será que ele é parente de um palhaço que faz vídeos na internet que tem muitos seguidores no Brasil? Como é possível que um sujeito tão ignorante (não de saber teórico, não no domínio de escolaridade, mas no de bom senso, maturidade, curiosidade, vontade de se informar de acordo com o que seria possível) possa chegar a um cargo desses? Não existe senso de ridículo no Brasil?

Ruy Salgado

07/01/2019 - 14h46

Do not be so full of yourself minister. It is Whittgenstein that do not like you.

Zé Pereira

08/01/2019 - 08h13

Sua segunda frase tem um erro crasso de concordância.