On AlJazeera

(Photo: Former President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, with former President Dilma Rousseff, at the headquarters of the Metalworkers’ Union on)

Why Lula’s conviction, like previous attempts to control the political crisis in Brazil, is unlikely to work.

by Rodrigo Nunes

5 hours ago

The Portuguese word “golpe” has a polysemy that is lost in English: It means at once coup d’etat, swindle and physical blow. One needs all three meanings to make sense of what has been happening in Brazil since Dilma Rousseff’s impeachment in 2016.

Unlike the military takeover of 1964, this is not a clean break with a pre-existing institutional order, but the cynical exploitation of institutional meltdown. Nor is it a centralised, full-fledged masterplan to contain social reforms and implement a conservative agenda, even if it has managed something of the sort.

Rather, it started as a slapdash attempt by a political class cowed by a gigantic corruption scandal and facing an ever-deepening legitimacy crisis to stabilise the political system while giving up as few as possible of its privileges.

Its outcome, however, has been much like that of someone trying to balance themselves on a rocking boat – each new ad hoc solution failing and thus perpetuating overall instability, bringing forth more swindles and blows.

After current President Michel Temer took over, a wiretap recording emerged of leading politician Romero Juca laying out the strategy to bring down Rousseff as part of a “great national pact” to “stop the bleeding” caused by corruption investigations. This politician was a member of Temer’s cabinet and had been a major figure in the administrations of the Workers’ Party (PT). Crucially, in the leaked conversation there was talk of involving PT in the pact so as to “protect [former President Luis Inacio] Lula [da Silva], protect everyone”.

PT’s reaction to the ouster in parliament was far more ambiguous than that of its social base in the streets. The paradigmatic moment came when the Supreme Court ordered the president of the Senate to step down on the eve of a vote that would result in a 20-year public investment freeze.

The Senate’s vice president, a PT senator, made it clear that he didn’t intend to take the seat and, if he did, the vote would go ahead as planned. In the end, the acting president simply refused to resign, and the Supreme Court meekly backed down.

The vote went ahead and one of Temer’s key austerity measures was passed.

When ‘stability’ measures destabilise

Such measures were essential to the “national pact”: a deal in which the political class would take advantage of the collapse of PT’s popular and parliamentary support to enact a pro-business legislative blitzkrieg, while big capital would provide the cover for their attempt to stifle investigations and steady the rocking boat. Or, to put it differently: in which politicians would exploit their very lack of legitimacy to pass measures repeatedly defeated at the ballots in exchange for a modicum of legitimation from those who stood to gain.

While most of the reform programme did go through, three things made the system impossible to stabilise. The first was the fact that the investigations attracted too much attention and stifling them became less feasible.

The second was that the assumption that Lula’s star would fade under the weight of allegations proved false. The economy continued to splutter, Temer’s cabinet looked like a corruption all-star team, the reforms were unpopular – all of which made the Lula years seem increasingly better by comparison and kept him solidly ahead in the polls.

It is true that the possibility of jailing him was always on the table, and that he was always the main prize for part of the judiciary and the public. On the other hand, arresting someone of his stature meant setting a precedent that most high-ranking politicians in Brazil would rather avoid. All of PT’s top cadre, entangled in the Petrobras scandal themselves, would have been amenable to a deal.

In the end, it was Lula’s continued electoral strength and the fact that the centre-right still can’t seem to come up with a single viable candidate, in the end, that made his imprisonment inevitable.

So why didn’t he drop out? And why does the PT insist on his candidacy even now? Neither had any choice but to go for broke: the party – because it has no real replacement for Lula and faces potential ruin without him; and Lula – because his electoral capital was the best shield against the corruption charges.

But once a commitment to playing by agreed rules is broken at the very top of the political system, with a president being ousted on dubious grounds, the lack of respect for the game contaminates everything. Rules and procedures become facultative, the law is applied ever more selectively, everything becomes a matter of interest or inclination, small despots spring up everywhere, and abuses of power, more than tolerated, are applauded.

Pandora’s box has been opened. It is this environment of institutional meltdown that has enabled a lower court judge to record and divulge a conversation involving the then president; the president of the Senate to stare down a judicial order and force the Supreme Court to retract it; judges to openly act as political operators, and higher courts to revise their own precedents at will; an intervention by the military in Rio de Janeiro to be declared in order to distract from a vote the government couldn’t win; protesters to open fire against a bus carrying a former president; and a high-ranking general to emit what many read as a veiled threat on social media before the Supreme Court voted on Lula’s appeal – all of which without fear of punishment.

It is the same feeling that everything is up for grabs and the law of the jungle is the only one universally observed. And all this explains why the assassins of Marielle Franco believed they could get away with murder. Almost a month later, their gamble is still paying off.

Then, of course, there’s Lula’s conviction. Though it stretches plausibility to think that he could have been unaware of what went on in Petrobras and how his party’s campaigns were funded, the actual case against him involves a number of questionable points in both procedure and content. As with Rousseff’s impeachment, however, it was clear that once it got going the outcome was a matter of politics more than a matter of evidence.

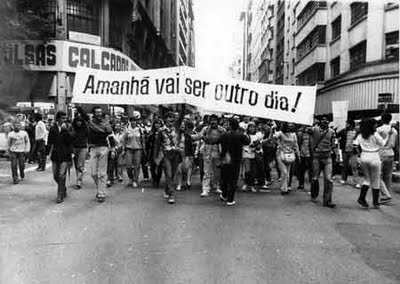

Still, by turning his arrest into an act of public defiance, however, Lula managed to turn what opponents expected would be a final humiliation into something of a symbolic victory, rekindling memories of the old firebrand among his supporters and strengthening the image of persecution.

Bad news for the centre-right, which might now have to sacrifice one of its own to deflect accusations of judicial partiality. They still lack a candidate for the presidential elections and could resort to new political manoeuvres to influence the vote, or forge an alliance with the far right, whose candidate is currently polling second

This is not necessarily good news for the left, however, as its fate is now tied even more to that of a jailed leader, further delaying the necessary reckoning with the mistakes of the recent past. Besides, how far the galvanising effect of Lula’s last speech has travelled beyond his traditional base is something yet to be gauged.

Politics as an elite sport

Swindle by swindle, blow by blow, Brazil staggers on, and nobody seems to have an endgame in sight. The increased lack of trust that actors will abide by the rules, the further demoralisation of already demoralised institutions, the explicit reduction of everything to a relation of force – that will be this period’s lasting, most dangerous legacy.

To the left, it has signalled that even someone with Lula’s conciliatory record might be fair game if the occasion arises. To the elite, it has suggested that, once it comes to tests of strength, the country is still theirs to rule by whatever means necessary. To the political class, it has shown that survival is possible if you play your cards right. To an emboldened far right, it has strengthened the belief in force and authority over debate, due process and the rights of minorities.

While many would present this as the dawn of a new age in which no one is above the law, it’s just as likely to be the opposite. Depending on what happens next – and predictions are futile in a system that unstable – this period may have confirmed to the population at large that politics is an elite sport; that it is only the weak who have to play by the rules; and that transparency, accountability and responsiveness have moved not closer, but farther away.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.

Nenhum comentário ainda, seja o primeiro!