by Simon Romero, New York Times

RIO DE JANEIRO — Students are taking over Rio de Janeiro schools to protest crippling education cuts, while the politician who helped bring the Summer Olympics to this city is battling allegations that he pocketed millions in bribes.

Grenade blasts from drug-gang battles echo through Leblon, the seaside bastion of the city’s elite. Even the governor’s daughter was recently mugged at gunpoint outside her home.

When Brazil’s new leader, Michel Temer, took the reins of the nation this month — a milestone in the caustic fight to oust President Dilma Rousseff, who faces an impeachment trial — he promised a new day of “national salvation.”

But what Mr. Temer did not mention is that his political party and its allies have wielded immense power here in the oil-rich state of Rio de Janeiro for most of the past decade — and this place needs a whole lot of saving, too.

In other words, critics lament, the same party that created a mess in Rio is now running the country.

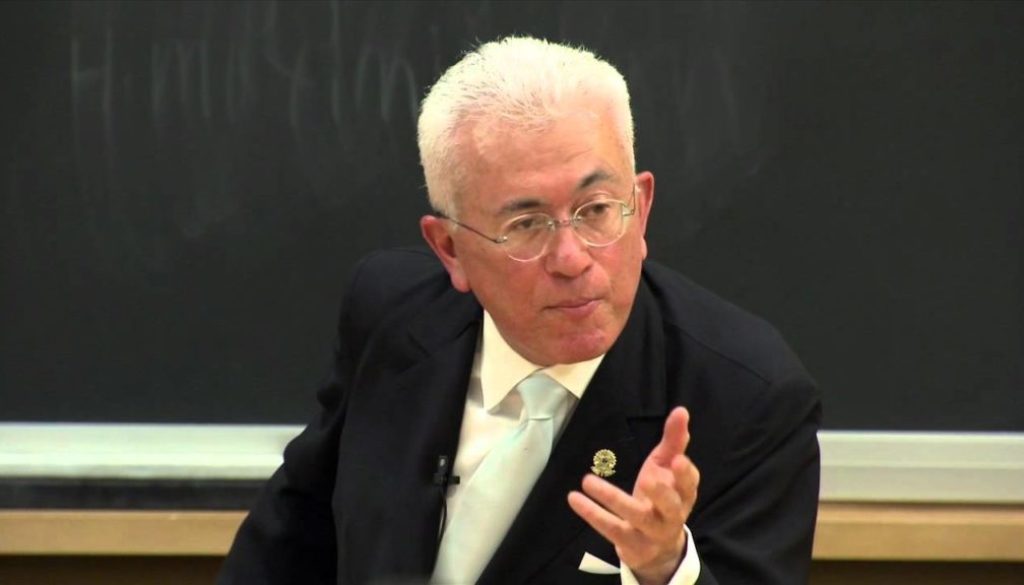

“Rio is evolving into a mini-Venezuela as its leaders find new ways to squander Brazil’s greatest oil bonanza,” said Marcelo Portugal, a Brazilian economist.

The state’s finances are a shambles. Some athletes are so disgusted with the City of Rio’s sewage-infested bay that they want the Olympic sailing races moved. Last month, a stretch of a new $12 million bike path flowing gracefully by the coast — one of Rio’s signature upgrades for the Games —collapsed after being hit by a wave, causing two men to plummet to their deaths.

“This is everything that we did not want happening at this moment,” said Rio’s mayor, Eduardo Paes, a prominent member of Mr. Temer’s party. “It’s not easy to host the Olympics in the current Brazilian environment.”

Rio’s leaders had promised that the Olympics would showcase Brazil’s triumphs. Instead, as Mr. Temer scrambles to put Brazil’s economy on stronger footing, Rio is emerging as a cautionary tale of what a government led by his Brazilian Democratic Movement Party could mean for the rest of the nation.

Some of the top leaders in Mr. Temer’s party — including the head of the Senate and the former speaker of the lower house of Congress, who was forced to step down this month to face graft charges — have been accused of accepting enormous bribes.

But their party, known as the P.M.D.B., is also coming under fire over accusations of mismanagement and graft involving the Olympics.

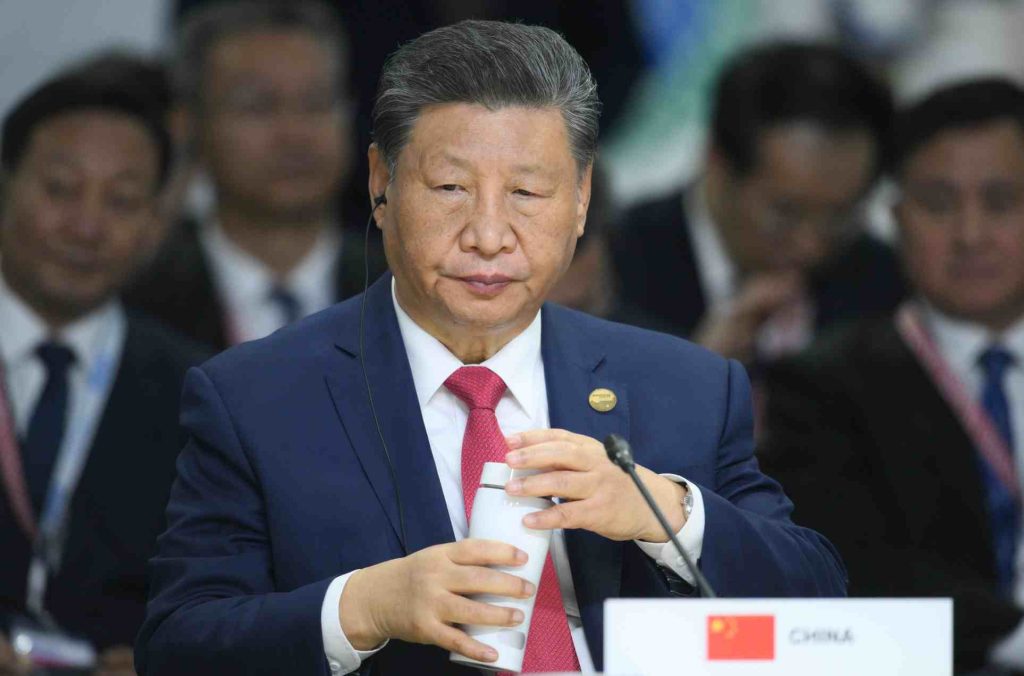

Engineering executives have testified that Sergio Cabral, the former governor from the party who helped land the Rio Olympics and still exerts considerable sway, demanded millions in bribes. They say the payments were the equivalent of 5 percent of the cost of the renovation of the landmark Maracanã soccer stadium and other public works projects.

Mr. Cabral also came under scrutiny for using the state’s helicopters to transport his children, their two nannies and the family dog on weekend jaunts to a beach house.

“Rio’s politicians are absolutely disgusting,” said Leonardo Siqueira, 37, a cosmetics distributor. He cited the collapse of the bike path, graft scandals involving public works projects and streets that flood with sewage during rains.

“Rio is in this crisis because of the P.M.D.B.,” Mr. Siqueira said. “They are politicians who govern first and foremost for themselves, not for the citizens.”

In a statement, Mr. Cabral said that he never took bribes and that his security advisers suggested using public helicopters to avoid potential attacks from drug gangs.

Under Mr. Cabral, Rio carried out a polarizing “pacification” campaign to police the city aggressively and alter its notorious reputation for crime.

But that, too, is coming under strain, with a crime wave marked by muggings throughout the city, an increase in the homicide rate and a terrifying surge in killings of children by stray bullets. In one tragic episode, a 1-year-old boy in a suburb was fatally shot this month while in his car seat.

Then there is Rio’s financial crisis, which is occurring despite the revenue from deep-sea oil fields off its coast. The undersea wealth helped turbocharge the regional economy just a few years ago, thanks to legislation giving state and local governments access to a trove of royalties.

Now Brazil’s oil industry is in turmoil as Petrobras, the national oil company, reels from bribery scandals and low energy prices.

Petrobras, based in a huge Brutalist headquarters downtown, has fired tens of thousands of employees over the past two years, sending a chill across other industries. Rio’s share of oil royalties is plummeting to about $1 billion this year, from $3.5 billion in 2014.

Rio’s leaders say the fiscal crisis has forced them to delay pension payments to retired state employees. The education budget was slashed, prompting teachers to strike and high school students to occupy more than a dozen schools to protest deplorable conditions.

Some factors in Rio’s crisis are beyond the state’s control, like global oil prices and the weak national economy. But wings of government have preserved their privileges while services suffer.

Judges recently won a ruling requiring the state to pay them before honoring other obligations. At the other end of the social spectrum, leaders are cutting back. A program created five years ago to provide cash subsidies of about $22 a month to about 200,000 of the state’s poorest residents ran out of money this month.

“I feel deceived as a cabinet member and revolted as a citizen,” Paulo Melo, the state official in charge of antipoverty programs, told reporters. He condemned the state government’s “generalized callousness.”

Leaders from the P.M.D.B., a largely centrist but ideologically malleable party that provided a facade of democratic opposition during Brazil’s military dictatorship from 1964 to 1985, had vowed to reverse the decline that characterized Rio after the national capital was moved to Brasília in 1960.

In 2007, Mr. Cabral took the helm of the state government, which oversees major functions like the police. Altogether, the State of Rio has a population of 16.5 million, almost the size of Chile.

Mr. Cabral, 53, nurtured an alliance with the governing Workers’ Party of Ms. Rousseff, enabling Rio to land the Olympics and secure federal funds for projects like a subway expansion.

In 2009, the P.M.D.B. also took control of the City of Rio, which has about 6.3 million people. The mayor, Mr. Paes, 46, embarked on a frenetic urban overhaul to highlight Rio on the global stage, refurbishing parts of the old center and installing light rail.

In the P.M.D.B.’s favor, most venues for the Olympics have been completed, easing concerns about Rio’s preparations for the Games, in August. On a national level, Mr. Temer has named respected economists from outside the party to important posts. And party leaders say they have provided a “moderating force” in Brazil’s tumultuous democracy.

“The P.M.D.B. is a pillar of governability,” said Renan Calheiros, the head of the Senate.

Here in Rio, Mr. Paes emphasizes that the city’s finances are in better shape than the state’s. Still, his administration faces accusations of ineptitude involving some Olympic projects, highlighted by the collapse in April of part of the new coastal bike path.

Protesters in Rio, as elsewhere in Brazil, have long complained that their leaders have prioritized lavish mega-events like the Olympics and the World Cup while neglecting essentials like hospitals and schools. It was a central grievance in the protests that shook the nation three years ago.

Now, people wonder about Rio’s capacity to solve its problems.

Mr. Cabral’s successor, Luiz Fernando de Souza (known by his nickname, Pezão, or Bigfoot), who took office in 2014, also came from the P.M.D.B. As Rio’s problems intensified, Mr. de Souza seemed unusually focused on a painting that hung in his office, “Death of Estácio de Sá,” depicting the agony of the Portuguese military officer who founded Rio in 1565.

Complaining about negative energy emanating from the painting, Mr. de Souza called it “really heavy” and had it removed. A few weeks later, Mr. de Souza, 61, revealed that he was battling non-Hodgkin lymphoma and went on medical leave.

His absence left the lieutenant governor, Francisco Dornelles, in charge. A veteran from the Progressive Party — which hews to conservative ideas and is closely allied with the P.M.D.B. — Mr. Dornelles, 81, has suggested suspending interest payments on Rio’s debt to ease the state’s woes.

“The P.M.D.B. and its allies have simply run Rio into the ground through their mixture of corruption and stunning incompetence,” said Marcelo Freixo, a prominent state legislator.

The self-described pro-business leaders of the P.M.D.B. in Rio are now embracing policies commonly found in leftist countries. To raise money, the state’s leaders approved taxes of nearly 20 percent on offshore oil production in Rio’s waters.

At a time of low oil prices, opponents say, the measure could destroy Rio’s oil industry. “The tax makes most of the projects in Rio unviable,” said Antonio Guimarães, the director of the Brazilian Association of Oil Producers.

Despite the grim assessments, some in Rio draw on the city’s history of resilience. Ruy Castro, 68, an author, told the magazine Veja that Rio had an “unrivaled capacity to frustrate those who root against the city.”

He then added a dash of skepticism. “We’re good at partying,” Mr. Castro said. “Not at legacies.”

Paula Moura contributed reporting from São Paulo, Brazil, and Mariana Simões from Rio de Janeiro

Nenhum comentário ainda, seja o primeiro!